Photographers:

John Anderson

John Anderson Photo Galleries

Ken Havard

My Bird Gallery & Flickr gallery 1 & Flickr gallery 2

Patrick Ingremeau

TAMANDUA

Ian McHenry

My New Zealand Birds

David Nowell

GALLERY

Illustrations:

John Gould: 1804-1881

John Gerrard Keulemans (1842-1912)

(Illustrations used by Walter Lawry Buller in “A History of the Birds of New Zealand” – 1888)

Text by Nicole Bouglouan

Sources:

HANDBOOK OF THE BIRDS OF THE WORLD Vol 14 by Josep del Hoyo-Andrew Elliot-David Christie - Lynx Edicions – ISBN: 9788496553507

KNOW YOUR NEW ZEALAND BIRDS by Lynnette Moon - New Holland Publishers – ISBN: 1869660897

BirdLife International (BirdLife International)

New Zealand bird status between 2008 and 2012

Wikipedia, the free encyclopaedia

Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Tiritiri Matangi Open Sanctuary

New Zealand birds and birding (Narena Olliver)

Tiritiri Matangi Open Sanctuary

CALLAEIDAE FAMILY

Saddleback, Kokako and Huia

The family Callaeidae is endemic to New Zealand and includes three genera for five species in the order Passeriformes. Only three species are remaining today, the two saddlebacks and the North Island Kokako. The second Kokako (South Island) is probably extinct since 2007, in spite of some sight reports. The fifth species, the Huia, is extinct since the early 20th century.

There are significant differences between the birds of the same genus suggested by genetic studies, but in addition, both saddlebacks (Philesturnus) and kokakos (Callaeas) from North and South Islands shows different behaviour, breeding biology and vocalizations, although they have very similar appearance, except some details in colour of wattles and plumage.

These birds, including the extinct species, have fairly short rounded wings, long rounded tail, and distinctive fleshy wattles at gape, blue or orange, becoming brighter and bigger during displays.

Both kokakos have bluish-grey plumage with cobalt-blue wattles (Northern species) and orange wattles (Southern species), a strong, down-curved black bill and long tarsi.

The saddlebacks have black plumage with chestnut “saddle” on the back extending to the rump. The wattles are red-orange and the black bill is strongly pointed.

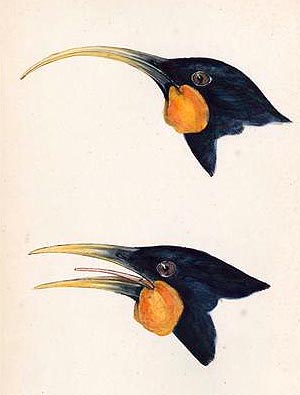

The Huia had black plumage overall, and a long black tail with broad white terminal band. The rounded wattles were bright orange. The female’s bill was longer and more down-curved than that of the male, but both had ivory-white bills. The long legs and the feet were bluish-grey. This species was the largest member of the family with a length of 53 centimetres (saddlebacks: 25 cm – kokakos: 38 cm).

Huia

Female above

Male below

In all species, the females are slightly smaller than males, and have smaller wattles.

The juveniles are duller than adults. In the South Island Saddleback, the young is very different from adults. It is entirely brown whereas in North Island Saddleback, the juvenile is a duller copy of its parents.

They are not particularly gregarious. They are usually seen alone or in pairs, and in small family groups after the breeding season. Foraging groups of about ten birds are sometimes observed in autumn.

The kokakos are shy birds, like the extinct Huia. In contrast, the saddlebacks are calling continuously.

The Callaeidae are more often heard than seen, and can be identified by their songs in the early morning. They sing all year round, but especially during the breeding season to attract a mate, and during territorial behaviour. They produce melodious organ-like sounds, but the song of the North Island Kokako is a haunting and mournful series of notes, while the saddlebacks utter harsher chattering which can be a series of loud notes, or shorter series of soft flute-like sounds. The extinct Huia produced peculiar and strange whistles described as soft and melodious. Both sexes sing and perform duets.

They are omnivorous, but the diet may vary among the five species, according to the shape of the bill.

The short down-curved bill of the kokakos is made for eating vegetation such as fruit and leaves, but also flowers and buds, and occasionally nectar and invertebrates. It regularly moves, following the food resources.

The saddlebacks are insect-eaters and use the strong, pointed bill to forage in the leaf litter and in rotting wood, probing among decaying wood and bark of trees to locate the hidden invertebrates.

However, the extinct Huia with different bill-shapes in male and female was fond of the larvae of the Huhu beetle (Prionoplus reticularis), an endemic species of New Zealand. The male was able to break up rotten wood with its chisel-shaped bill, while the female was probing into holes and bark crevices with her longer, more down-curved bill.

Huia

Female above

Male below

They are forest-birds and were formerly living in lowland and montane native forests of New Zealand. They are mainly found today in regenerating forests on offshore islands. The species translocated to offshore islands have adapted to unfamiliar habitats such as exotic forests.

The North Island Kokako prefers tall mature hardwood forest dominated by tawa (Beilschmiedia tawa) whereas the South Island Kokako was commonest in high-elevation beech forests (Nothofagus).

South Island Kokako above

North Island Kokako below

The translocated saddlebacks occur in lowland beech forests and mixed evergreen forests. Indications from fossil evidence suggest that the North Island Saddleback is adaptable to coastal and montane shrublands.

The Huia occurred in mixed hardwood and podocarp forests, and sometimes beech forest with dense understorey.

They are monogamous and have long-term pair-bonds. The mates often remain together for the life. They maintain the territory throughout the year by calls and songs, threat displays with chases and occasionally physical fights. The territory is an important area where they forage, breed, roost and live all year round.

They breed during the austral spring and summer, and all are solitary nesters.

The courtship displays include the typical “Archangel-Displays”. The male is perched on tree or on the ground. It raises the wings and moves them rapidly in front of its mate. It may carry some vegetation in the bill, but these items are repeatedly dropped. The saddlebacks usually lead the female to a chosen nest-cavity after these displays.

They perform courtship feeding throughout the year, but more often during this period, and this behaviour is used to reinforce the pair-bonds.

All the displays are accompanied by calls and songs.

All the Callaeidae build a cup-shaped nest with sticks and twigs, grass, leaves, moss and lichens, and lined with softer materials. The female builds the nest alone.

The saddlebacks are cavity-nesters and build the nest inside a hole, a tree cavity in trunk or large branch, in rock crevice and even in nest boxes, occasionally on the ground. The kokakos nest among branches of trees and shrubs, usually ten metres above the ground. The Huia built a large saucer nest placed in varying places such as tree fork, dead tree, and hollow in tree, and even near or on the ground, and it was sometimes covered with hanging vegetation.

All these nests are usually well-concealed among vegetation, either high in tree or on the ground.

The clutches often consist of 2-3 eggs, but single-egg clutches are natural too. The female alone incubates and broods the chicks, while the male feeds her on the nest. The incubation usually lasts 18-20 days but it is unknown for the Huia, probably ranging between 16 and 28 days.

The chicks are fed by both parents and fledge between 25 and 37 days according to the species. The young birds still depend on parents for food for some days after fledging, but often for longer period.

Nest failures are caused by small introduced mammalian predators such as rats, mustelids and possums. In the offshore islands free of predators, the failures are due to natural avian predators.

The Callaeidae adults are sedentary. However, they may move to neighbouring territories when water or food resources are restricted. The juveniles often disperse over 1-2 kilometres before to establish their own territory close to their natal area.

It is suggested that the Huia was an altitudinal migrant, but the frequency of these movements is unknown.

They are weak fliers and cannot sustain the height. They only fly over short distances. However, they often use their long legs to propel themselves through the canopy or across the forest floor with long leaps.

Decline and extinction of the members of the family Callaeidae were caused by predation by introduced mammals and habitat destruction and fragmentation with forest clearance.

The South Island Kokako was officially declared extinct in 2007, and the Huia disappeared in the early part of the 20th century.

The North Island Kokako is listed as Endangered, but intensive conservation measures would allow the increase of the numbers from 750 to 1000 pairs by the year 2020.

The North Island Saddleback is currently considered Near Threatened, but the population of 6000/7000 individuals is suggested to be increasing.

The South Island Saddleback’s numbers are slowly increasing and estimated at 1200 individuals, and the species is considered Near Threatened.

The translocation of birds from mainland islands to several offshore islands free of predators, allowed the increase of the populations. Thanks to intensive management of populations and predator control, the numbers of the three extant species of Callaeidae are slowly increasing in their new habitats. Some of them are still present on mainland islands, but they have adapted to their environment on offshore islands.

We hope they will remain for long time the distinctive endemic birds of these beautiful islands.